01

/

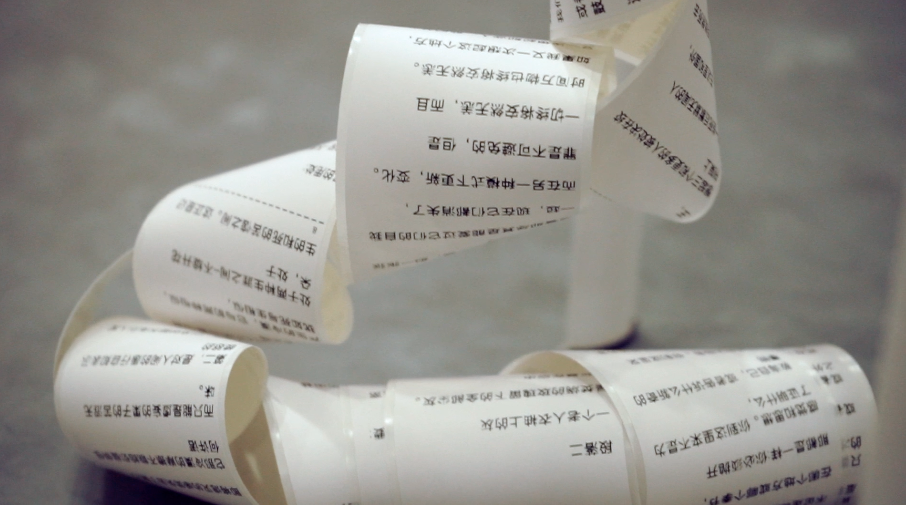

Enituor, or the Everyday (2022), video still, single-channel video, 5 min. 47 sec.

Enituor, or the Everyday (2022)

By spelling the word "routine" backward, Enituor is a video-collage playing on the inverse/reversal of the everyday routine. It explores the perception, encoding, staging, and remembrance of everyday experiences. With its composition of various video clips, it delves into the meaning of visual reflections, coincidences, and humor found in cracking encoded spaces, objects, and events, with deliberate parody or defamiliarization of the mundane.

On Enituor, or the Everyday (2022)

Zhangxinan Wu

The video collage, Enituor, or the Everyday, is a composition of numerous video clips that reflect upon the ways in which the everyday is perceived, encoded, staged, and memorized (or forgotten). As a patchwork, or a mishmash of contexts and discourses, Enituor is concerned with the meaning of visual reflections (as retina images), the moment of everyday coincidence and fabrication, the humor in the cracking of those encoded everyday space, objects and events, as well as the deliberate parody or defamiliarization of the everyday.

The enigmatic term in the title, Enituor, is a coined word from the spelling of “routine” in reverse, which indicates that our attempts to capture, represent, or signify the everyday very often counteract the intention, therefore always walking on the verge of a reverse of the everydayness. Similar to what Yasmin Ibrahim talks about how banal imaging “strings everyday life,” “chronicling the routine normality of the everyday and life’s mortal passage where the pace rhythm and the rituals of daily living are composed through imagery” when discussing instagram photo-genre of routine images, daily vlogs also tend to provide familiar everyday codes, convention, and processes (45). However, instead of intervening directly with daily vlog as a video genre, Enituor patches up many scenes and moments that seldom appear in the genre. While a vlog usually entails indoor scenes, with numerous registers of exclusive space, characteristic Lo-fi pop music as background, and a clean and warm tone of color (intentionally matched throughout), Enituor tends to be open, porous, sometimes chaotic in its selection of clips and its way of stitching them together. If the word routine, according to OED, implies a sense of mechanical and normative way of being, Enituor is serendipitous, instinctual, and cluttered.[1] It does not go along with the morning-to-night temporality, and sometimes intentionally staging everyday indoor actions to the point that they essentially lose their everyday register, as a way of accentuating both the orchestration in the vlog genre and the deliberate ritualization of the everyday through cinematography.

The collage is divided into an A-side and a B-side part—similar to that of phonograph records or cassettes—which foregrounds a sense of materiality. Yet now materiality does not lie in the product, but in the process of the practice. The question of materiality becomes also notable when we think of how, as Ibrahim discusses, the “non-stop need to “commodify everyday life” always underlie those daily routine images (42). One could not help but ask: is there a way to approach the essential materiality of the world without ever being devoured by the force of commodification? Through art practice and processes, is it possible to work on art with a resistance to product-oriented mentality?

The two parts of the video collage are composed of clips collected in two cities—Beijing and New York, one being where I was born and raised, the other being the place of sojourn for my current existence. The clips in the first part are primarily collected out of whim during the time when I was in Beijing during the early stage of Covid-19—they are mostly not-yet-used videos, somehow discarded precisely because of their everydayness and their ambiguous narrative (or even the total lack thereof). In this part, scenes are not sought after. They are like found objects on the street that one simply picks up during her everyday encounter: including a person burning joss paper for ancestral worship—an uncommon scene in the urbanized metropolis; the reflection of the world on a smart phone—a device that normally projects rather than receives light from the surroundings; along with some normative (if not mundane) street scenes—which nevertheless looks defamiliarized when they are posed upside down as retina images are supposed to be.[2] What is being experimented here is a way of stitching (as opposed to editing) and collecting (as opposed to selecting) of relations that simply emerge, rather than relations that are strained to the point that they lose their underlying intertwining.

As the collage starts with a scene of water in reverse, followed by a series of upside-down clips, this rendering gestures to a play of the idea of inversion (as the title Enituor plays with the idea of “reversal”), as well as the mechanism of perception. It tends to remind us of how the everyday is perceived as retina images, and how strange it is to see these images as they are—being presumably upside-down if not processed further by the optic nerves. The humor lies in that, through eliminating certain perceptual processes and thereby getting seemingly “closer” to reality itself, the inversion of everyday images seems just as unreal and unfamiliar to us. Meanwhile, with gravity being the law that prescribes all sides of our earthly life, the upside-down scenes, especially those with nature elements (e.g. water, fire, and wind), become unfamiliar to us, if not almost unreal, as biped beings on the terra firma—note also how these images may remind us of our immanent relation to gravity, especially in the post-Apollo 11 era: Fire was flowing downward, whereas water was weirdly attached to the upper edge of the screen—scenes that may arouse strange embodied affect and responses.

Here I am hesitant in agreeing with Blanchot that the everyday is not about scenes in nature. According to Blanchot: “The earth, the sea, forest, light, night, do not represent everydayness, which belongs first of all to the dense presence of great urban centers,” or that “the everyday is not at home in our dwelling-places, it is not in offices or churches, any more than in libraries or museums. It is in the street—if it is anywhere” (17). When Blanchot argues that everyday is human, what is human does not lie in the site itself, but in the way how relations, including the unwelcoming ones, are established through perception. The A-Side and the B-Side, through stitching up the scenes either of nature or indoors on purpose, are trying to challenge the boundary of the idea of the everyday. The everyday can be expansive and extremely fluid. It infiltrates into every layer of life as long as processes of perception and reflection are involved. Even when these clips were collected serendipitously, the everyday is now reverted, inverted, and turned (vert) into something that is on the edge of being/not being our daily experience.

The soundtrack of the first part, too, alludes to life here and there, shifting and drifting among a variety of contexts and discourses: the sound of turning on the stove at the beginning of both parts, the sound of bird chirping, water sparkling, street artist’s performing, people talking, of machine working, sirens, NYPD announcement, etc., along with a poem excerpt (attached in the Appendix below). The poem excerpt is itself a collage, with breath and intonation embodied through the voice yet compressed in a way that resembles that in a phone call. Just like the video itself, the poem piles up moments and instances of the everyday. The soundtrack, likewise, is a mishmash of recordings of those moments of everyday life. In terms of sound, weaving and knitting—the childhood passion of mine—are still the approach in dealing with the immanent intertwining of everyday soundscape. The working process is illuminating as a listening practice. Audio clips are, as the clips in the A-side, composed of “found objects,” yet the almost indistinguishable boundaries between layers of sound also makes one realize how sound is always inclusive. It is always a mishmash, and always already woven in our daily life, whereas the limit of visual perception sometimes lies precisely in its exclusive capture.

While the A-Side is composed of found scenes of the everyday life, the clips in the B-Side, by contrast, are mostly staged on purpose, yet in a way that disrupts what is commonly seen in daily routine vlog: such as scenes of taking out keys from a plastic box, wilted flowers and moldy apples, leaves on a pan on stove, a drawing of a plate of fruit (with a reference to Matisse’s work, Interior at Nice, circa 1924) on the lamp, a drawing of cloud—which is supposed to be amorphous and constantly changing—now put aside with a pot of life plant, or charging cords in between pappardelle and vermicelli noodles, etc.[3] These staged scenes are claiming the non-everydayness of the everyday from several different ways. The perishable flowers and fruits, for instance, are almost never taken as part of a routine vlog, whereas their decay is such an integral part of the everyday. However, on the other hand, as long as they are staged for cinematic purpose, the sense of messiness and perishability becomes inevitably tempered and aestheticized. Even this underside of the everyday, which is supposed to have potential to be a critique of cinematic aestheticization, becomes alienated and somewhat smoothed out by the capture. One tends to ask: does perishability (and along the same line, mortality) lose its everydayness because of photographic or cinematographic varnish? Here we may also add another twist: as Jean Baudrillard points out the “murderous capacity of images,” the tension then seems to arise between the eternalization and the murder of everyday images (170). Probably because of the transient and amorphous nature of the everyday life, what cinematography cannot help but do is killing off the everyday precisely through perpetuating it, as well as the other way around—perpetuating it by murderous rendering.

In this sense, the working process itself is also a reflection on the inevitable alienation of cinematic images. The more camera tries to approach the world, the more it seems to distance itself from the world. Camera makes the world an object. There seems to be always the limit of camera in capturing the mingling and entanglement of the world—the intertwining because of which a binary between the subject and the object can hardly apply, and the boundary between things and space simply falls apart. Camera (lucida) offers us illusions as it disillusions the one who tries to approach it.

Another way of playing with daily routine genre in the B-Side is pushing the role of cameraman/woman as an orchestrator, choreographer, or director to its very limit, and thereby foregrounding how everyday is staged. Strange scenes such as autumn leaves in a pan on stove, or a video clip of a meal in the center of the plate of that meal itself, are intentionally orchestrated. Not only are they in great contrast with the clips in A-Side, but they point more directly to the aggression of everyday experience. As noted by Susan Sontag, “Those occasions when taking of photographs is relatively undiscriminating, promiscuous, or self-effacing do not lessen the didacticism of the whole enterprise . . . there is an aggression implicit in every use of the camera” (7). This sense of deceptiveness seems to be more pronounced in video, as it always tricks its audience by adding to it the flow of time. Along this line, the deliberate staging of scenes in the second part tries to come out more straightforwardly as a failed self-effacing attempt. It gestures to unveiling the aggression in the use of the camera, yet still falls into the trap of a backfire. It can be said that the A-Side and the B-Side each focuses on one of the two phases (out of four phases in total) that Baudrillard lists in “Simulacra and Simulations”: the former as the reflection of a basic reality, and the latter as what masks and perverts a basic reality (170).[4] Yet the demarcation is not settled. Reflection and perversion are always entangled fields.

Moreover, the B-Side plays with defamiliarizing the everyday also in a self-reflexive way: it plays directly with lenses and glasses, for instance, in a scene where eyeglasses were hang on the nexus of criss-crossed cords—alluding to how light come through (and the cords themselves are USB charging cables that are able to conduct electric currents), as well as in another scene where eyeglasses get in the way between the camera and the lamp on the table that the lens tries to capture. In the latter case, the scale of the lamp is changing, making it a little bit dizzy to look at. There is an interest in how the eye works, as well as how lens (physical and mechanical) and camera works. Another scene where sparkling water functions as a filter for the camera similarly gestures to unfamiliar daily moments with everyday object. The everyday is being perceived, now in a way that self-reflexively foregrounds its approach where certain distortion and inversion are always there without leaving noticeable traces.

Collage as a form indicates a way of perceiving the everyday when it always tries to escape from us as well as from itself. It suggests a different spacial-temporal sense which memory and life are predicated upon. Its refusal of clear, coherent narrative and those intentional and disproportionate gaps, chromatic mismatches, and clashes between liminal space and outer world audio recordings (e.g. on a New York City subway train) signify the texture and the complex of the everyday. There is a moment where the NYPD announcement becomes the voiceover of a clip of two dancers and friends of mine—Shuyi Liao and Yann Tie—were bumping into each other. In the stitching-editing, the video and the audio come together as a pure coincidence. I was surprised when I saw this weird match—or mismatch—by simply dragging a recording into the editing software. Now the contact-or-clash between two bodies in a clip of dance improvisation connotes something that is beyond itself, including strange sexual innuendo and a sense of confrontation that verges upon violence. It seems that the narrative of the police is changing the way we interpret and understand moments of life. At the same time, the coincidence also conveys a sense of humor—you never know what comes to you, and how the everyday can be warped by that which, simply, just comes.

The patchwork both holds and resists the intention to merge and submerge narratives. Here one comes to the question of authorship, as well as the approach: what is the relationship between the camera-woman and the everyday that is (sometimes, or never) in her capture; how to do away with, or is it ever possible to do away with certain kind of aggressive, egoistic recording and editing of the everyday; or if the the patchwork itself, without the deliberation of the author, has its potential of reference, signification, and contextualization; if working with camera gently can again become hypocritical and self-cheating—as a way of hiding away from its underlying bourgeois mentality, yet still always with a touch of the middle-class and academic isolation from what is really on the ground. These questions can be always difficult and troubling, yet still a good place to start with in one’s art-making. It seems ironical if this introduction betrays certain desire of controlling the potential of the work. After the rambling, perhaps the best way to not killing off the work is to leave it as it is—as the reflection/inflection, reversal/inversion/perversion of the everyday.[5]

[1] Routine as defined in OED: “A regularly followed procedure; an established or prescribed way of doing something; a more or less mechanical or unvarying way of performing certain actions or duties” (https://www-oed-com.proxy.library.nyu.edu/view/Entry/168095).

[2] Between A-Side and B-Side, there is also another clip that tries to defamiliarize us with our daily use of up-to-date gadgets, a moment when audience were amazed by how Steve Jobs scrolled on the first iPhone in 2007 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Etyt4osHgX0&t=487s).

[3] If Wallace Stevens would remind us that “The clouds preceded us” (“Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction,” I.IV, 311), the drawing of cloud points to how far representation has gone from the first cloud, if there is ever one.

[4] Here is the original list of Baudrillard: “These would be the successive phases of the image: 1. It is the reflection of a basic reality. 2. It masks and perverts a basic reality. 3. It masks the absence of a basic reality. 4. It bears no relation to any reality whatever: it is its own pure simulacrum” (170, italics mine). Enituor plays primarily with the first two phases. In addition, as the A-Side offers a series of upside-down images, there is also a play on the word reflection at different levels.

[5] Note: The project reaches out to many directions that I would like to further explore. Due to limited time, it seems that the collage itself may not have brought out all of them. My initial plan was to have the video as simply part of a multi-media performance, staging the clips on several different digital gadgets/devices such as projector, TV, computer, and tablet. This might be an option for its further form. I would also like to go on recording the everyday encounters, experimenting with more ways of weaving in and out the immanent intertwining. The voice-over of the poem in the A-Side was written quite some time before the project, and used more ad hoc here. There might be a way of writing that serves the project differently. The theoretical approaches can be elucidated further for the project, yet the project for now itself has taken more time and effort. Hopefully these directions will grow as then are in the coming future, if future is a word for what is to come.

02

/

Reading a poem of Douglas Dunn (2021), video still, single-channel video, 2 min. 42 sec.